[This post was originally published on Plus10Damage December 19, 2012.]

I began a ritual last Halloween. No, not the Satanic kind. The kind where I annex myself to my room, close the door, and shut off the lights. I sat atop my bed, my laptop placed strategically on my lap, so as to occupy as large a percentage of my vision as possible. The donning of my Grado SR-80i headphones completed The Preparations. Well, not quite. There was yet one integral element: I had to open Steam, select Amnesia, and press “play.”

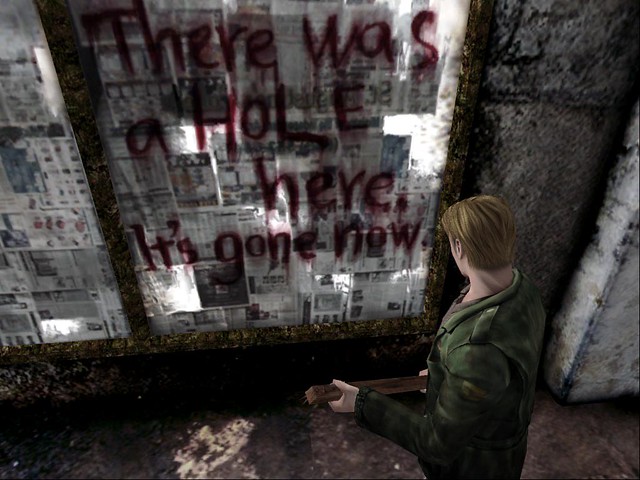

And for what? Why take extra effort to frighten myself? Why go to all this trouble, if I’m just going to end up breathing heavily and closing the game in a couple hours? Why do I keep pushing back in, if I know my mind will be unable to withstand the isolation and subsequent terror? Condemned, Amnesia, Dead Space, Anna, Silent Hill, Fatal Frame, F.E.A.R., Alan Wake, and even parts of Bioshock have played a role in this strange ongoing quest to torture myself.

Why?

WHY?

By genre definition, a horror game is meant to terrify or inspire “horror.” This is accomplished by tricking the mind — much like in film — that something completely and obviously made-up is actually happening. AND TO YOU.

This is immersion, and horror games have it. They have to have it, or they fail. Emphasis on atmosphere and psychological play are two of the most important elements to consider when creating the scarytimes. Atmosphere pulls you in, and the way you interact with the atmosphere — the gameplay — has to be fine-tuned not for ultimate fun, but tension and fear. I hate to say that it’s “more of an art,” mostly because I’m afraid I haven’t given such a broad statement nearly enough forethought, so I’ll stick with something simpler.

In my experience, horror games are consistently the most immersive.

That. That is why I keep coming back to them. That is why I perform tedious preparations — I actually lit candles once while playing F.E.A.R., so as to create further shadowplay — in order to fully enjoy the pants-peeing. Horror games demand the most intense immersion from a player in order to be successful, and work hard to establish such an atmosphere.

There exists one problem in every tension-and-then-scare-you-to-death-fest I’ve ever encountered:

The immersion break.

Death, specifically. In horror games, death is the worst. Let’s use Amnesia again to exemplify this concept, since it was while playing Frictional’s terrifying masterpiece that I wrapped my mind around this truth.

The water level. Without spoiling much — if anything — there’s an invisible beastie capable of awful noises and splooshy steps coming after you. But only when you’re in the water. It’s terrifying, because every trip to the next platform is a tense race against the filthy aberration that constantly pants and sniffs in its search for your delicious meat-body. In the moment, I was terrified of nothing more than ghostmonsterguy getting me from behind, and doing hell-knows-what to my poor, should-have-tried-harder-in-gym-class corpse. In fact, it made my heart race literally more in sheer terror than anything ever has in any game.

It is nuts. I hate it. My nerves hate it.

But then the guy gets me, an interface pops up and basically screams “you’re in a game sucka,” and I have to try again. All of a sudden, the creature that induced sheer terror has transformed an obstacle that I must outwit. It’s still tense, sure. But my brain has remembered something very important, something that — in the rush of immersion — it forgot.

It remembered that it was playing a video game.

While horror games are the industry’s champions in terms of immersion, that immersion is often fragile and, when destroyed, leaves a shell of an experience. Without narrative to propel a horror trip that has no immersion factor — the F.E.A.R. sequels — the game falls pretty flat. I want to have some great idea about fixing this from a developmental standpoint, but removing actual character death / failure seems almost impossible. In fact, it’s that impending death that propels such terror in the first place. Perhaps we lovers of the frightening will just have to deal with the fact that, after all, we’re playing stories. And those stories are always going to have limitations.

But hey. Come Halloween, I’m going to try to mentally transcend those limitations.

And maybe poop myself.

[This post was originally published on Plus10Damage December 19, 2012.]